20.03.–09.08.2015 | Kumu Art Museum

The current exhibition is a modest homage to Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935) on the 100th anniversary of his iconic 20th-century painting Black Square. Without any pretensions to exhaustive treatment, it is an attempt to display an intriguing and multifaceted selection of various interpretations of Black Square in the works of Estonian artists.

Malevich himself dated Black Square 1913, the year in which he, the poet Alexey Kruchenyck and the painter and composer Mikhail Matyushin collaborated on the Futurist opera Victory over the Sun. According to Malevich, the geometric stage designs of the opera gave rise to the idea of Black Square. The painting was in all likelihood completed only in the summer of 1915, as the visual manifesto of Suprematism: a painting system created by Malevich. It embodied the abandonment of the tradition of art as imitation of nature, and strove to set autonomous rules of abstract art. Malevich exhibited his Suprematist works for the first time in December 1915 at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings ‘0.10’ [Zero, Ten] in Petrograd, where he placed Black Square in the “corner for icons”, showing it as superior to other works of art. Black Square was also featured on the cover of the booklet explaining the concepts of Suprematism, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism (1916). In the booklet, the painting was extolled as “the first step of pure creation in art”.

“The zero of form”, a visual tabula rasa, Black Square is a supremely simple image, yet its meaning remains open: in the eyes of the author, it simultaneously served as the primal element of the new art and as the symbol of the unlimited potential of the avant-garde aesthetics. In the 1920s, Malevich started to view Suprematism as a universal system, a model for redesigning the living environment, beginning with accomplished projects of objects and interior design and ending with visions of the new architecture and cosmic apparatus. The motif of a black square often formed the core of Malevich’s designs; he made several author’s copies of the Black Square painting (in 1923, 1929 and around 1931, as far as is known), and also used the symbol to sign his correspondence and works of art. Malevich’s pupils wore black squares on their sleeves and it could also be found on the artist’s coffin above his head and on his gravestone.

Thus, Black Square became an essential part of Malevich’s artistic mythology; in a wider sense, it symbolised the radical nature of the avant-garde, inescapable in the discussions of both modern and post-modern art. The first replicas of Black Square were made by Malevich’s students during his lifetime; more recent interpretations in Russian and Western art are innumerable. Black Square has become the cornerstone of contemporary art, which cannot be ignored by any aspiring artist: one either has to try to comprehend it or rebel against it as a fetish of the art world through deconstruction. Thanks to numerous homages and citations, Black Square crossed the borders of the field of meaning given to it by its deceased author long ago: it has become an autonomous character, taking on an independent existence in the works of other artists. This process was cleverly captured in the title of the exhibition by the State Russian Museum – The Adventures of the Black Square (2007) – which was also an indirect source of inspiration for the idea of our exhibition.

Artists of Estonia have contributed to the narrative of Black Square over time in different media, taking an approach that is characteristic of a specific author or era. Malevich’s contemporaries, the Group of Estonian Artists, were more interested in the Cubo-Futurism and Constructivism of the Russian avant-garde. Despite that, we can find the motif of the black square in a painting in Kumu’s permanent exhibition: Arnold Akberg’s View from Toompea Hill (1924), in which the depicted woman wears a black brooch. At the current exhibition, the black square is in the centre of Akberg’s Construction (1928), forming the starting point for the whole composition. The motif of a black square or rectangle in book illustrations from the pre-World War II era is tied to the geometric aesthetics of the international avant-garde movement, which was to a great extent influenced by El Lissitzky, a student of Malevich’s.

The first Estonian artist to systematically study and introduce Malevich’s ideas was Leonhard Lapin, after World War II. His conceptualist art is largely based on Suprematism and contains both heroifying and ironic interpretations of Black Square. In the series Forms (2004) by Andres Tolts, Lapin’s fellow member of the SOUP ’69 artist group, the black square is just one of the many motifs to surrealistically impinge on the bureaucratic world of Soviet blanks. An earlier, although possible rather than direct reference could be Ülo Sooster’s illustration for the collection of articles Физика: близкое и далекое (Physics: Near and Far, Moscow, 1963), which visualises the consecutive derivation of information units. The illustration does indeed show a black square, but it remains uncertain to what extent Sooster was thinking of Malevich’s work. The problem of unavoidable associations with Black Square in contemporary cultural consciousness is highlighted in Flo Kasearu’s project Politics of Space (2014; in collaboration with Alexander Roslin, Jaan Rõõmus and Ronald Uus), in which a black rectangle or square was added to empty spaces on the personal ads page of the Õhtuleht daily.

The installation Black Square Fade (2014) is a result of a printing session. The author Kiwa was primarily looking for a simple shape of uniform surface, which would change colour and eventually “disappear” as the printer cartridge emptied. The inescapable connection to Malevich’s painting has made the theme of the nullification of the image only more powerful. The fact that Black Square has become an archetype that cannot be avoided when dealing with the subject of the void, disappearance or infinity is apparent in Ats Nukki’s meditative/contemplative works. Kiwa’s other works included in the display develop the links between Black Square and the theme of emptiness in the key of ironic playfulness, touching upon the issue of the symbol becoming an empty signifier in today’s information flow and pop culture. Villem Jahu’s Execution (2006/2008) addresses Black Square directly and actively, as it depicts the last stage in the opposition to authority, which can only be followed by patricide.

The painting Starting Position (2009) by Enn Põldroos cannot be clearly identified as a reference to Black Square; however, it fits well with the theme of Black Square as the starting point of contemporary art. Sharper social subject matter is introduced by Aleksei Gordin’s diptych Black Square (2014), which shows the view that opens in front of a bum peeking into a waste container. Hanno Soans’ work/gesture Absolute Nafta I (2003) is an homage to Alexander Brener’s iconoclastic action: in 1997, Brener drew a green dollar sign onto Malevich’s original painting in order to criticise the turning of the avant-garde leading figure’s legacy into a monetary equivalent. Soans, in turn, added a golden dollar sign, which reminds one of both money and icons, to a work by Sirje Runge, the Estonian classic of minimalist painting.

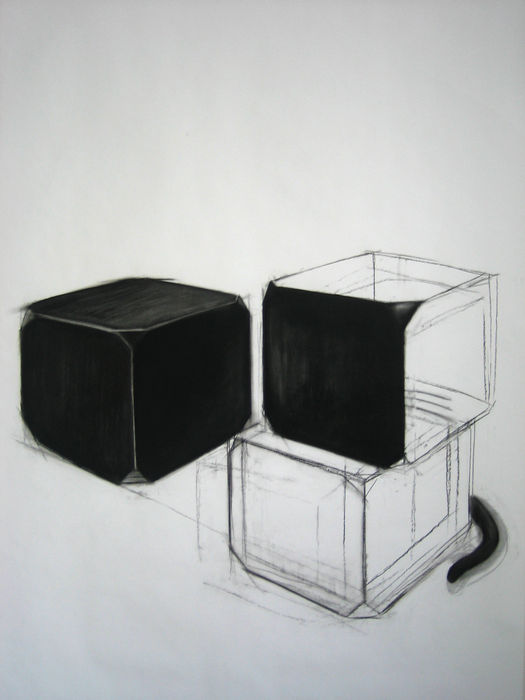

Sirja-Liisa Eelma’s Malevich’s Black Cat (2006) is an artistic research project that plays with the connections between different shapes and words. A playful research-analysis is performed in theDeconstruction of Malevich’s “Black Square” (2000/2010) by Janno Bergman, who derives, in the spirit of Malevich’s theoretical charts, a formula of potential elements of Malevich’s work. Tanya Muravskaya’s photo diptych has been created specifically for this exhibition and develops the theme of identity, which initially emerged in her self-portrait from the series Positions (2008). It merges the subject of the body of the artist and Black Square as the symbol of conflict, as well as persistence, and aspiration.

The exhibition is accompanied by a display of Black Square-themed publications at the library of the Art Museum of Estonia. Our thanks go to: Leonhard Lapin

Curator of the exhibition: Elnara Taidre

Designers of the exhibition: Raul Kalvo and Helen Oja

Graphic design: Külli Kaats

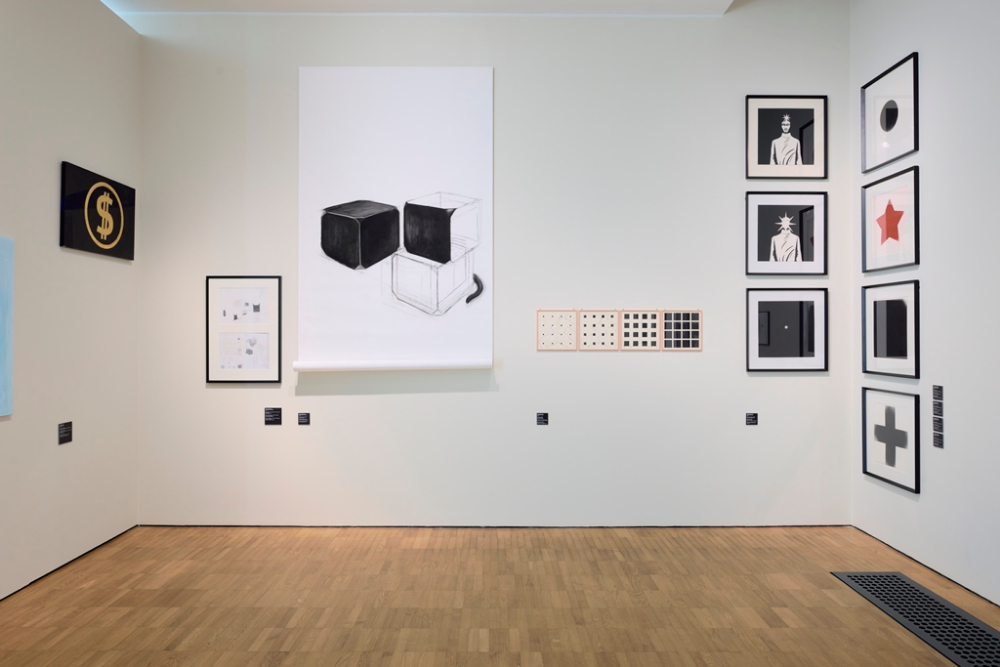

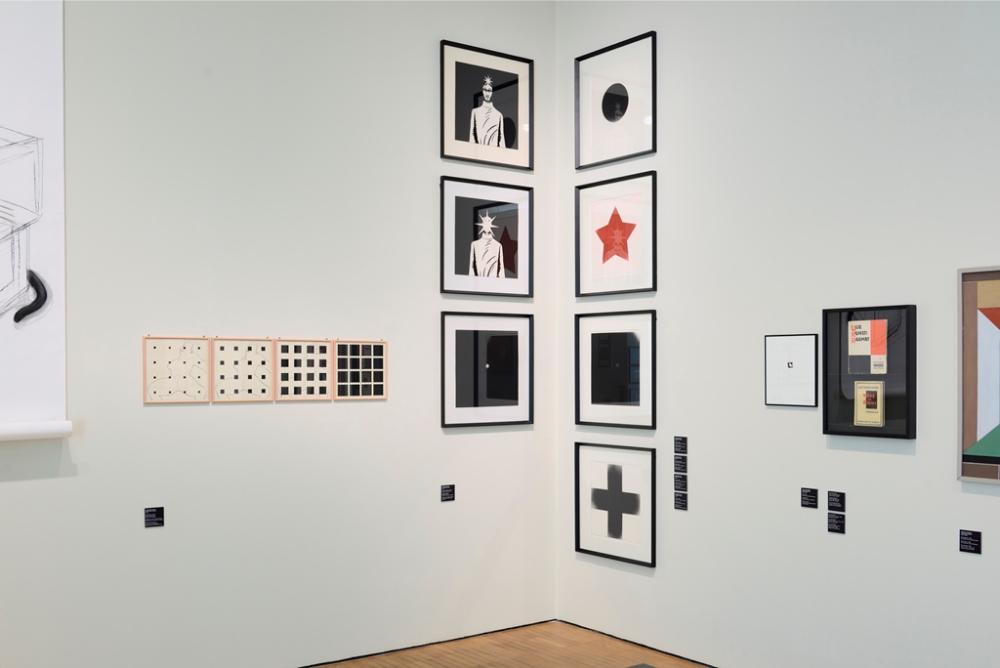

Metamorphoses of the Black Square. Interpretations of Malevich’s Work in Estonian Art, KUMU Art Museum, 2015, exhibition view. Photograph by Stanislav Stepaško.

Metamorphoses of the Black Square. Interpretations of Malevich’s Work in Estonian Art, KUMU Art Museum, 2015, exhibition view. Photograph by Stanislav Stepaško.

Tanya Muravskaya, Untitled/Self-Portrait, 2015, photographic diptych, 2015, digital print. Courtesy of the artist.

Tanya Muravskaya, Untitled/Self-Portrait, 2015, photographic diptych, 2015, digital print. Courtesy of the artist.

Metamorphoses of the Black Square. Interpretations of Malevich’s Work in Estonian Art, KUMU Art Museum, 2015, exhibition view. Photograph by Stanislav Stepaško.

Metamorphoses of the Black Square. Interpretations of Malevich’s Work in Estonian Art, KUMU Art Museum, 2015, exhibition view. Photograph by Stanislav Stepaško.

Sirja-Liisa Eelma, Malevich’s Black Cat/Box, 2006, charcoal. Courtesy of the artist.

Metamorphoses of the Black Square. Interpretations of Malevich’s Work in Estonian Art, KUMU Art Museum, 2015, exhibition view. Photograph by Stanislav Stepaško.

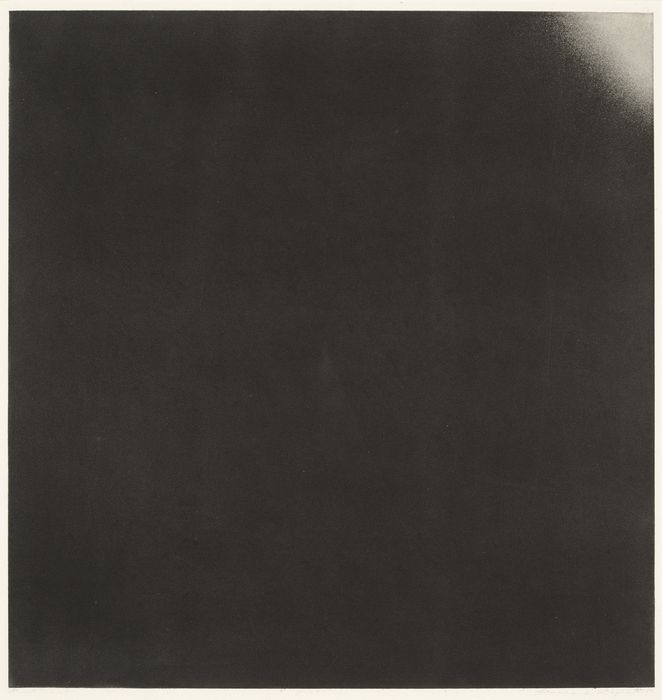

Leonhard Lapin, Black Square, 1980, intaglio. Courtesy of Art Museum of Estonia.

Metamorphoses of the Black Square. Interpretations of Malevich’s Work in Estonian Art, KUMU Art Museum, 2015, exhibition view. Photograph by Stanislav Stepaško.

Villem Jahu, Execution (part of the installation), 2006/2008. Photograph by Vaiko Viitmann. Courtesy of the artist.